3 Minutes with Linda, Author of How to Recognize a Demon Has Become Your Friend

Original Photo by Riccardo Bertolo from Pexels

We have the great pleasure of sharing 3 minutes with Linda D. Addison, author of How to Recognize a Demon Has Become Your Friend, HWA Lifetime Achievement recipient, SFPA Grandmaster, and all around ray of light. See what all the fuss is about in the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle for just a few more days (until July 2nd).

Describe this work in 3 words.

Entertaining and educational.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism is a self-affirmation that being Black and writing/painting/sewing/singing ourselves into the Future; in a present world that too often denies us past/present/future representation.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

This collection was created while I was struggling with the death of my mother (from illness) and didn’t see when I would write again. Putting this together was suggested by Bob Booth, so it began with reprints, but helped me start writing new work for the book.

What subject do you find most difficult to write about?

I started my career writing more SF and fantasy because I grew up in a fearful environment. It was difficult to face the shadows to write horror; in time I’ve learned to come to terms with that past, which has helped me write horror themed work.

Do you have any writing tics?

I like to write with music, but music without words since my imagination is activated by words.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

Everything influences my work. I have been journaling since 1969, so I write everything down; bits and pieces of poetry/stories and my feelings about the world around me. When writing new work, I go to my journal entries for inspirational seeds to build on.

How do recent challenges of the day (the pandemic, post-Trump/post-Brexit) inform what you’re working on right now? Do they affect the context of this work? If so, how?

I lost half a year in 2020 to covid symptoms/long hauling, surviving that has increased my gratitude at life and confirmed what I’ve always believed: humans can be amazingly loving and/or fearful messes.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

It’s more that I can’t not write than anything else. I tried stopping many years ago, when rejections were piling up, but the inner pressure to write couldn’t be denied.

3 Minutes with J.S., Author of Queen of Zazzau

Original Photo By Breston Kenya from Pexels

Kicking off the final week the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle will be available, we have J. S. Emuakpor to share her views Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic mean and could mean as well as more about her work.

Describe this work in 3 words.

African history reimagined.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism is not so easy to define, because it is both a noun and a verb to me. It is a movement as well as a product. Afrofuturism is what lies ahead for the African diaspora. It’s our endpoint, our “Ultimate Form.” It is the African diaspora as seen through the lens of Speculative Fiction.

How do you define the Black Fantastic?

The Black Fantastic or Afrofuturism. Which came first? I think, in this case, the relationship is not linear. The Black Fantastic refers to the manner in which Blackness has shaped and reshaped popular culture across the world. It is so completely intertwined with Afrofuturism that the two concepts are often interchangeable. The Black Fantastic, like Afrofuturism, is a noun and a verb. It is also an adjective. Frankly, Black Fantastic is who we of the African diaspora are.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

The most difficult part of Queen of Zazzau to write was the god of war. When he and I started his journey, I could only see him through the eyes of my protagonist, and she hated him. He was cold and seemingly cruel. Until, one day, I looked into his heart and saw him for what he truly was. After that, I had to figure out a way to keep his edge without the reader hating him, because he wasn’t the awful person that I had believed him to be, and I didn’t want the readers to think that he was. Fine-tuning his interactions with the main character was difficult, but I think I succeeded.

What’s on your desk?

The real question is: what isn’t on my desk?

What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism and/or the Black Fantastic go? What would you like to see come of this moment of greater recognition?

I would like to see more mainstream speculative fiction written by and featuring the African diaspora. I would like to see the Afrofuturism/Black Fantastic movement spur real change in the way people of color are viewed by the world. I want the world to know that we are so much more than what *they* tell us we are. We are accomplished, we are brilliant, and we can slay orcs as well as any Tolkien hero.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

Everything I come in contact with influences my work. But mostly, I am influenced by the Nigerian culture in which I was raised. Our myths, our fears, our superstitions. All of these things are present in my writing.

What are you working on now?

I am currently working a few projects. Two are in the same series as Queen of Zazzau and will feature African gods and monarchs. The one that has been getting most of my time in the past few weeks, however, is a world-hopping, steampunk, with a side of interracial romance. I thought it would be a straightforward story, but there’s a lot more world-building going on than I had anticipated.

3 Minutes with Nicole, editor of Slay: Stories of the Vampire Noire

Original Photo from Pixabay/Pexels

Welcome the weekend with a closer look at Nicole Givens Kurtz, editor of Slay Vampire Noire and publisher of Mocha Memoirs Press. Below find a bit more about her and delve deeper into the work featured in the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic Storybundle available until July 2nd.

What’s your general approach to choosing works for an anthology?

My contribution to the Afrofuturism bundle is SLAY: Stories of the Vampire Noire.It is a collection of short stories that feature vampires or slayers from the African diaspora. My approach for choosing the works for this anthology involved seeking stories that had an emotional impact. Stories that lingered long after I had finished reading and stuck like peanut butter, their flavor continuing to permeate long after I’d ingested their content. Of course, I looked for clean drafts and well-rounded stories where the protagonist had agency and was from the diaspora, but the story’s impact mattered more to me with this anthology.

How do you define Afrofuturism?

I define Afrofuturism as creative art (music, art, writing, film) in which those of the African diaspora are depicted prominently in futuristic or alternate settings. An important aspect of Afrofuturism is in its ability to transcend one type of creative outlet. It’s in music, it’s in film, books, lifestyles. It’s a broad term, to be sure, but I think of it as an umbrella to which the other genres gather.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

Readers and my own stubbornness keep me writing and editing. There are times when the load gets heavy, and I consider putting it down. Publishing is a difficult and challenging industry. My publishing company, Mocha Memoirs Press, has been around for 11 years now. Each year brings new challenges and struggles, and I have considered quitting–many times. Yet what sustains me are reader responses to our works, and my own stubbornness not to give up. I often feel the *break* I need and the press need are just around the corner, so I cannot stop–even when I have rounded many, many corners. LOL.

What are you working on now?

Currently I am working on a science fiction romance story. I just completed draft 0 of a horror novella that may or may not see the light of day. LOL. Mocha Memoirs Press continues to publish bold, fearless fiction. I encourage readers to sign up our newsletter and check out our blog for updated releases at mochamemoirspress.com.

3 Minutes with Michele T. Berger, author of Reenu-You

Original Photo by Lennart Wittstock from Pexels

Michele T. Berger, author of Reenu-You, shares its origin story, what’s next for her, and her influences. Reenu-You and the other fine work in the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic bundle is available until July 2nd.

What’s the first Afrofuturist/Black Fantastic/Black Scifi work you read? What was the last?

I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved in college and I consider the novel an example of the Black Fantastic. It’s a literary ghost story that ruminates on being, Blackness, death, slavery, memory and history. I read it in a literature class. The novel made an impression on me. The most recent Afrofuturist work I’ve read is Rivers Solomon’s stunning novel The Unkindness of Ghosts. It, too, ruminates on many of the themes explored in Morrison’s work.

Why this story?

Reenu-You is a speculative story with elements of psychological horror that explores what happens when a mysterious virus is seemingly transmitted through a hair care product billed as a natural relaxer. Reenu-You grew from several sources of inspiration. One was watching the drama unfold of a real hair product called ‘Rio’, marketed to women of color in the 1990s. Rio promised an easy and healthy alternative to other products on the market. Soon though women began reporting horrible reactions to Rio including itchy scalps, oozing blisters and significant hair loss. A class action lawsuit revealed that there was nothing natural, at all, about the product. It actually contained a number of highly acidic chemicals.

This news event grabbed me and gave me the inkling for the story. Over several years, I kept asking myself questions about why and how a scandal like that could happen and how different communities might respond to it. I speculated on the mindset of a company that not only deceived the consumer, but endangered their health. I also thought about the consumer, and what desires and longings Rio tapped into. Although I didn’t ever use Rio, I remember the seductive nature of their infomercials quite well. I, like other African American women, was transfixed by their upbeat, exotic marketing that promised an easy and healthy hair treatment.

In watching the events unfold, I thought about how trusting we are as consumers that the products we purchase will be safe. And, also how everyone in the 1990s started to fall for various items labeled ‘natural’. What if that wasn’t the case? What if a hair product that primarily women of color used harbored something deadly?

I’m also fascinated by viruses. I came of age during the height of HIV/AIDS and remember the terror, fear and stigma associated with the virus. For a long time there were conflicting reports about the transmission of HIV/AIDS and its origins. Often conspiracy theories and popular culture filled in the gap.

I wanted to play with the idea of conspiracy and how different communities might respond to a health crisis, especially before the era of ubiquitous cellphones and social media. A virus was a perfect fit.

Viruses are adaptable, disruptive and frequently are medical mysteries. In just the past two decades, we’ve seen Bird Flu, Swine Flu, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome), Zika, Ebola, and now COVID-19.

I’m also interested in the politics of beauty, female friendships and Black hair culture. In Reenu-You, I can play with these ideas by having different characters reflect on the complexity of their intimate and yet social choices. I love that I get to explore what fascinates and terrifies me, all in one novella.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Gish Jen, Ntozoke Shange, Octavia Butler, Charles de Lint, Jonathan Lethem, Ursula Le Guin and Elizabeth Hand are writers that I return to again and again to learn from about voice and craft. In the past decade, I’ve been most influenced by the work of Sherri Tepper, Margaret Atwood, Walter Mosely, and Kevin Canty. Writers that I’m currently obsessed with are Cynthia Leitch Smith, Amy Tan, Jeff VanderMeer, Nnedi Okrorafor and Joy Castro. I find myself drawn to the late 1970s and early 1980s (when I was coming of age) and to African American cultural history of the 1920s.

What’s on your desk?

I don’t have a desk. I have an Ikea table that I have made do with for more than twenty years. On it, I currently have two laptops (a Mac and Lenovo, both tend to get glitchy at the same time), precarious piles of papers, journals, post-it notes and the recent book by Gail Carriger, The Heroine’s Journey: For Writers, Readers and Fans of Popular Culture. I also keep heart shaped and gold star stickers at hand. As a fun reward after a session, I’ll put one on my writing calendar. In answering this question, I see I need a bigger reward—a new desk.

What are you working on now?

I’m three drafts into a horror novel that takes place in the North Carolina areas of the Great Dismal Swamp. Prior to the Civil War, the Great Dismal Swamp housed many fugitive slaves and maroon communities. The novel will be published in the fall by Falstaff Books.

3 Minutes with Bill Campbell, co-author of Baaaad Muthaz

Original Photo by @onyx-scopes on Nappy.co

We start the week with Bill Campbell, whose graphic novel Baaaad Muthaz (co-authored with Damian Duffy and illustrated by David Brame) brings the visuals to the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic bundle until July 2nd. Take it away, Bill.

Describe this work in 3 words.

Spacefunk Pirate Booty!!!

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

Baaaad Muthaz is an ode to Black music. However, record labels are very strict about quoting music lyrics, so it’s hard to refer to songs without actually using the lyrics. You can only use the songs’ titles. So, a lot of jokes wound up being untold.

What’s your favorite Afrofuturist or Black Fantastic work?

Ishmael Reed’s Mumbo Jumbo changed my world when I read it back in the day. It informed so much of what I do I’ll have to go with that.

Why this story?

I wanted to do something fun, and I wanted to celebrate the culture. We don’t spend enough time celebrating all the contributions we’ve made to this world.

How do you measure writing success?

There are certain challenges I put before myself with each project—something I don’t think I’d done before. So, if I’m able to pull whatever those challenges are with each project, I’ll generally consider that a success. I don’t know if outside markers really come into play so much (though your ego can play tricks on you) because writing, for me, is such a personal thing.

How do recent challenges of the day (the pandemic, post-Trump/post-Brexit) inform what you’re working on right now? Do they affect the context of this work? If so, how?

I just finished writing a Black superhero graphic novel project that’s heavily influenced by recent events, but I’m not ready to talk about it. It’s an absolutely insane ride, though. I can’t wait to share it with the world.

3 Minutes with Nisi, author of Talk Like a Man

Original Photo by Skylar Kang from Pexels

Next up is Nisi Shawl, making their 2nd appearance in an Afrofuturism bundle I’ve curated and for good reason. This time it’s their publication from PM Press’s Outspoken Author Series. Get your DRM-free copy of Talk Like a Man and the rest of the bundle here until July 2nd.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

In this book, the most difficult story for me to write was “Something More.” I occasionally refer to it as “the story that almost killed me.” It was inspired in part by the life and death of Sandy Denny, a self-medicating depressive and alcoholic folksinger, and I became deeply, deeply identified with her during the writing process. My editor, Timmi Duchamp, couldn’t parse the manuscript, which was full of sentence fragments and incomplete metaphors and delusions. She worked very closely with me to make it accessible, though I believe another editor would have simply given up on the mess.

Later, an ex of mine remarked that “Something More” is in conversation with Octavia Butler’s work–in particular, her novel Kindred. I hadn’t realized it at the time, but yes, obviously.

What subject do you find most difficult to write about?

I find it really hard to write about the sort of mass lynchings and racial traumas that inform this country’s history. Rosewood, Tulsa, Wilmington–I just can’t face or fictionalize them. I have to turn away quickly. The closest I’ve come to doing so is in Everfair, and that novel takes place on a different continent and describes an alternative history in which millions of deaths did NOT take place. I am in eternal admiration of Kai Ashante Wilson’s short story “The Devil in America,” which accomplishes what I could never hope to.

How do you measure writing success?

I measure writing success with a series of moving goalposts. There are always new firsts, always new challenges, new dreams to fulfill. There’s your first sale, your first sale within a particular genre, your first sale for a certain payrate, your first award, your first receipt of a particular award, your first piece of fanmail, first fan art, first hardcover, novel, screen adaptation….Success is a never-ending process.

What influences your work? People, other fields, other authors, events, histories?

My work is constantly influenced by everything around me: landscape, weather, health, family, politics. Artistic creators are a huge part of my environment, too, of course.

Writers of that ilk include Colette, Raymond Chandler, Samuel R. Delany, C.J. Cherryh, Georgette Heyer, James Tiptree, Jr., Cordwainer Smith, Nicola Griffith, Vonda N. McIntyre, Octavia E. Butler, Ishmael Reed, Peter S. Beagle, Suzy McKee Charnas, E. Nesbit, Edward Eager, Alice Walker, Margaret Atwood, Gloria Naylor, and George Eliot. Those are a few of the positive influences. But there are negative influences as well: those authors I write against, such as Barbara Cartwright. And some authors fall into both camps; Heyer’s antisemitism is outrageous, for instance, though I adore her facility with dialogue.

Music is crucial to me as an influence–so much so that I put together soundtracks for stories I’m working on. Here are the names of some of the musicians, bands, and composers I’ve turned to: Wayne Shorter, Jimi Hendrix, Steely Dan, Royksopp, Zero Seven, Chopin, The Boys of the Lough, Kekele, Tinariwen, Angelique Kidjo, Djelimady Tounkara, and Los Munequitos de Matanzas.

Finally, I’ve been watching lots of series and films on my phone for the last couple of years, and I hope the influence of their plotlines, arcs, and resolving tensions will be felt in my new work. Favorites so far include Peaky Blinders, Better Call Saul, and Outlander.

What are you working on now?

At the moment I’m writing another novel, Kinning. It’s a sequel to Everfair. I’m up to Chapter 12 of sixteen projected chapters. Two months to go till my deadline. Will I make it? Let’s see.

Love, Nisi

3 Minutes with Zig Zag Claybourne, Author of The Brothers Jetstream: Leviathan and Afropuffs Are the Antennae of the Universe

Photo by 3Motional Studio from Pexels

Zigs is bringin’ it. I’m gonna get out of the way. (If you want to hear more from this engaging mind and author of 2 books in the bundle, you can get the bundle until July 2nd).

Describe this work in 3 words.

“Oh, it’s on!” (3 more words: exciting, fun, real) (The Brothers Jetstream. For Afro Puffs, the 3 words would be “…and find out.”)

Have you witnessed the Black Fantastic or Afrofuturism in real life? If so, what was it?

Clearest recent example of Afrofuturism at work in my city, Detroit: to address the food deserts (lack of viable grocers) and the technology deserts (internet access—which should never have been commercialized in the first place–isn’t affordable for all, which places lots of Detroit students at a disadvantage) a group of Black community activists and tech activists came together and created free, secure wifi hubs in several of the most neglected areas of the city, along with donating computers. As for the food deserts, community gardens now dot the cityscape in the most beautiful of ways. These are two paths forward for those who faced brick walls. Afrofuturism is DIY. It’s attempting to find a harmonious way that might bring order to chaos.

What was the most difficult story/part of your novel to write? Why?

There’s a scene where a villain murders someone simply because they can. That sense of heartless impunity gutted me because way too much of our real world is exactly like that. People gone for no other reason than a person, a business, a community, a government—wanted them gone. Where’s the respect for our ineffable souls and the dignity of sentience? The story of humanity isn’t meant to be a tragedy.

What’s your favorite Afrofuturist or Black Fantastic work?

Parliament’s Mothership Connection. That entire album is a sci-fi novel spanning worlds, time, and dimensions!

Why this story?

This is the question that gets me bouncing like a hyped boxer. I’ve talked about it before (here for those interested) but short version: I personally wanted an epic tale about Black brothers constantly saving the world, one where they’re always doing it “one last damn time.” I looked for that epic tale. Something wild, something that poked fun at tropes but in a way that brought the reader along for the joke yet had heart. I couldn’t find one. So I squared my shoulders and wrote the ultimate adventure I wanted to read.

As for its sequel AFROPUFFS ARE THE ANTENNAE OF THE UNIVERSE: that was meant from day one to stomp male fragility. If I saw one more fanboi come for a sista (in particular, women in general) in genre…I was ready to act a fool. 2020 called for a story with an all-woman crew; an adventure where a shameless “Kirk” speech delivered by the captain of that crew felt right on time; a sci-fi story wherein idiocy got trounced like it owed everybody money.

Name one darling you killed before the final draft.

Fiona Carel. The crew in PUFFS are the women from The Brothers Jetstream: Leviathan. I wanted to bring Fiona Carel over from The Brothers Jetstream same as I did the crew. Fiona’s Irish, white, and sensitive to the multiverse. I wrote entire sections of her doing angsty multiverse stuff…but ultimately the story said nerp, not this time. As much as I love her character, she distracted from the Black Girl Magic this romp delivers.

What subject do you find most difficult to write about?

I’m not a fan of centering Black trauma, particularly in sci-fi/fantasy arenas. There’s this pernicious notion that pain is intrinsically and specifically tied to Black skin, be it on the Continent or via the diaspora, which tells me that regardless of the surrounding plot, the only story too many people want to hear from us is how we deal with the “pain” of being Black. Listen, I grew up listening to Earth Wind & Fire and Prince; I got the rhythms of the ancients in me! I can bring the thunder and lightning, but I play in the joyous rain.

What direction would you like to see Afrofuturism and/or the Black Fantastic go? What would you like to see come of this moment of greater recognition?

My hope is that readers realize Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic (which damn well needs to be a band name) are more than solely entertainment to pass the time, they’re building blocks to actual social change far past the status quo. Whether comedy, adventure, fantasy, drama, romance–art is meant to connect us to something more than we started with.

How do you measure writing success?

First, by how much fun I had with the story. Second, by how satisfied I am with the story’s soul upon completion. Third, did readers feel like I honored their time? Anything after that is whipped cream on top of pie.

What’s your approach to worldbuilding?

I’m a fan of the less-is-more approach. As a writer and a reader, I like to wander a story’s playground to find interesting toys and attractions. If I’m reading your zombie sci fi novel I don’t want a page of exposition telling me about the planet’s atmosphere, the evil mining corporation that abandoned folks, and the marital backstories of the two main protagonists. I want “There weren’t enough of us left to bury the bodies…”

What’s the first Afrofuturist/Black Fantastic/Black Scifi work you read? What was the last?

Dhalgren by Samuel Delany was the first, a book which opened me to wonderful new ways to tell a story. The Space Between Worlds by Micaiah Johnson is the latest, a wonderful journey through the multiverse. Both books share an expansive sense of scope and character, which I love.

What are you working on now?

In March 2020 I had a short story published at GigaNotosaurus about a mother and daughter witch team from a secondary-world version of Africa traveling the world. It was called “The Air in My House Tastes Like Sugar”. The characters spoke to me so much I wanted to see what they did next. Result? A fantasy novel about this mother & young daughter having the adventure of their lives.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

Questions. Not understanding things. Writing helps me see the world’s bones and tendons at work. I may leave this world not having figured a single thing out, but at least I can say I made the attempt.

3 Minutes with Zelda, Co-Editor of Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora

Original Photo from Pexels

While the Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic storybundle is going on (until July 2nd), I’ll be sharing a little about some of the editors and other authors in the bundle. Zelda Knight, coeditor of Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa and the African Diaspora kicks us off.

Describe this work in 3 words.

African / Diasporic Unity

Editors, what’s your general approach to choosing works for an anthology?

When selecting works for an anthology, I always go through a similar mental checklist: does it follow the requirements, is it on theme, and does it mesh well with other accepted works or offer a contrasting view? If a work satisfies all three, then I take the time to really dive in. I’m mindful of how hard it is to put something you created before a stranger’s eyes, and try to keep that in mind even when I have sharp critiques.

What compels you to keep writing/editing?

There are always new worlds to discover and voices that need to be heard. If gatekeepers aren’t going to publish them, I can’t complain that these stories aren’t being told when I have the expertise to make that happen. Indie presses and authors are always setting the mainstream trend.

The world is awash in terms right now: Afrofuturism, Africanfuturism, Black Speculative Fiction, the Black Fantastic, Astroblackness, etc. Do they matter? If so, do they do justice to the diaspora? If not, how might we as authors and editors lead a change? Feel free to offer any new terms you think would expand and/or deepen the concept.

I think so to some people. As long as authors are actually taking the time to properly cite the foremothers, forefathers, and so on of these terms (in particular Afrofuturism that is receiving a lot of undue criticism as of late), I don’t personally care. No one term can “do justice” to the diaspora because the African Diaspora is truly global, and many are created with specific experiences in mind. The experience of people of African descent are linked but not identical, you know? I’m personally of the philosophy that authors should (a) use what works for them, (b) respect the work of who came before them before launching critiques, and (c) the publishing world should take time to respect which labels people place on their own works. The last would be the real change.

What are you working on now?

I’m working on personal work in the sci-fi and fantasy romance realm all the time. I’d recommend my novelette, Zephyr’s Curse, if you want a small taste of the stories I tell. Anthology-wise, I’m co-editing a number of Afrocentric anthologies with Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki and Sheree Renée Thomas!

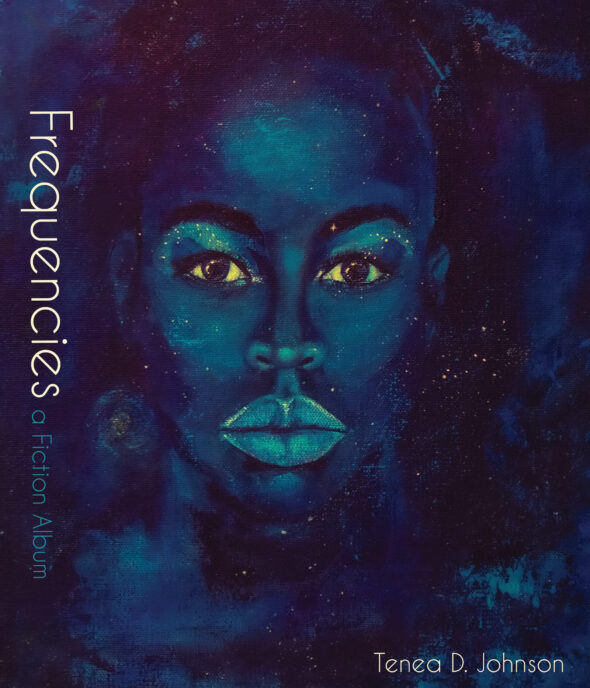

Frequencies, a Fiction Album Is Here

They’re all special to me but something a little different this time. Just between you and me, there will be a damn fine deal on this one next week, but for those who hate waiting, you can hear the opening now. And if you absolutely loathe it, you can get your own copy from a secure site, complete with a bonus track.

Cover Art by Kelly U. Johnson